The 2021 Atlantic hurricane season got off to a very fast start, with Tropical Storm Ana forming in May, Tropical Storms Bill, Claudette and Danny in June, and Hurricane Elsa in early July. Elsa was the earliest hurricane to form in the Atlantic deep tropics east of the Lesser Antilles of the satellite era, and passed near Barbados as a hurricane. Elsa made several landfalls along its path through the Caribbean, and eventually made landfall in northwestern Florida as a strong tropical storm. Since Elsa dissipated, the Atlantic has been very quiet, with no tropical cyclones forming for the latter two thirds of July. It looks like the period of quiet will last for at least another week or so, but this should not be taken as a sign of a quiet season. The month of July averages approximately one tropical storm a year, and is not part of the peak of hurricane season. With warmer-than-normal sea surface temperatures in the tropical Atlantic, and a weak La Niña likely to develop over the equatorial Pacific this fall, it appears likely that the Atlantic will have yet another above-average hurricane season. However, the signals have not been quite as favorable as last season at this time.

Atlantic Sea Surface Temperatures

The Atlantic is currently in an ongoing high-activity era of tropical cyclone formation that began in 1995. This high-activity era has typically been associated with above-normal sea surface temperatures over the deep tropical Atlantic and far north Atlantic. The eastern tropical Atlantic is currently warmer than normal, while the central and western tropical Atlantic has near-average sea surface temperatures. Despite this, the Atlantic lacks the classic “positive AMO” signature, with a large area of warmer than normal sea surface temperatures over the central Atlantic, and a patch of cooler than normal sea surface temperatures over the eastern subtropical Atlantic near the Canary Islands. However, it has been rare to see the classic “positive AMO” pattern in recent seasons, but it has done little to reduce overall Atlantic hurricane activity. It is possible that the warm sea surface temperature anomalies in the central subtropical Atlantic could slightly damper instability in the Atlantic Main Development Region (MDR), but it is doubtful that it will be a major negative factor in reducing the overall activity of the season. The Atlantic MDR is slightly cooler than 2020 at this time, but is substantially warmer than 2018 and fairly similar to 2016 and 2019. The warmest sea surface temperatures are relatively close to the equator, giving the Atlantic an unusual “Atlantic Niño pattern.” There is currently no meteorological consensus on whether an Atlantic Niño is a suppressing or enhancing factor of Atlantic hurricane activity, but it is likely to shift the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) farther south than it has been in recent years. This is reflected in climate models, which generally show reduced precipitation over the Atlantic MDR and Caribbean for the peak of the season (in contrast with 2020), with above-average precipitation farther south closer to the equator. Overall, since the tropical Atlantic is slightly warmer than normal, I’d expect the Atlantic sea surface temperature pattern to be a slight enhancing factor for the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season.

El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO)

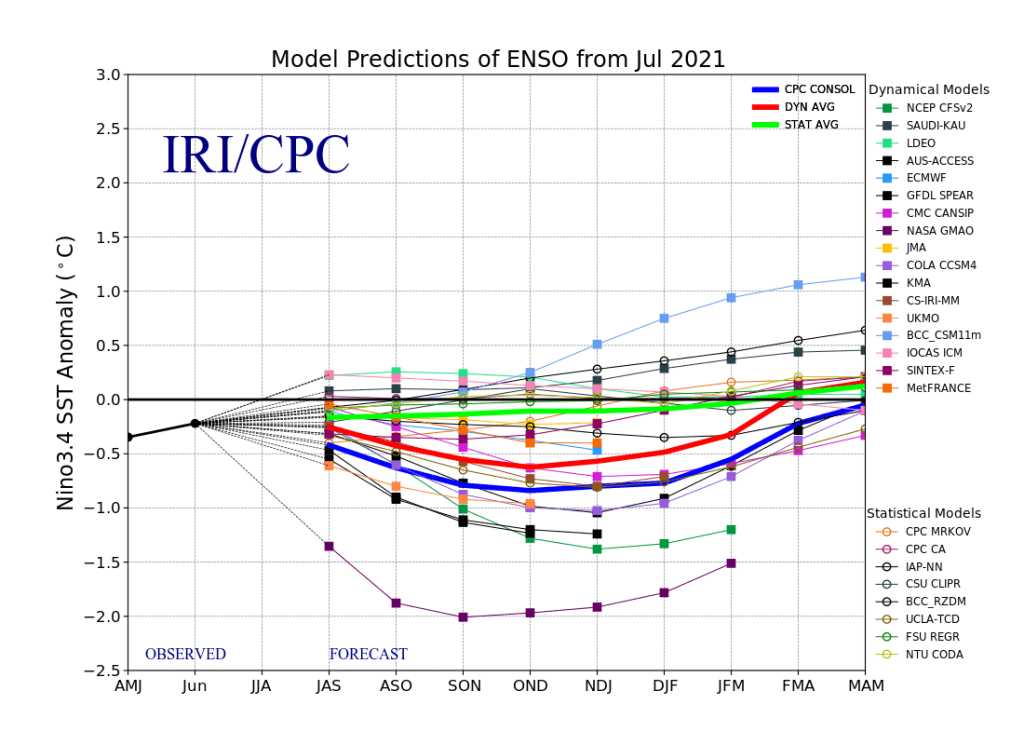

The El Niño-Southern Oscillation Index is currently in the cool-neutral range. The Climate Prediction Center (CPC) determined the moderate La Niña event of 2020-21 to have dissipated last spring, but overall the atmosphere has still resembled La Niña. The latest weekly Niño 3.4 value was -0.5°C, which is barely at the La Niña threshold. The 90-day average Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) came in at +6.53, which is near La Niña levels. The equatorial Pacific subsurface, after being warmer than normal for much of the spring and early summer, has cooled rapidly during the month of July. Without westerly wind bursts likely to cause significant warming of the ENSO regions over the next few months, there is now high confidence that ENSO will be either cool-neutral or in the weak La Niña range for the peak of the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season. Historically, cool-neutral and weak La Niña seasons are very favorable for Atlantic hurricane activity, especially in the deep tropics. This is because La Niña conditions usually results in the wind shear vector becoming more easterly over the tropical Atlantic, leading to reduced vertical wind shear. I’d expect ENSO to have a significant enhancing factor on the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season. If La Niña develops this fall, which appears increasingly likely, that will greatly increase the chance of late-season hurricane formation in the Caribbean Sea. The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, with moderate La Niña conditions, produced a record-breaking 5 major hurricanes after September, including two high-end Category 4 hurricanes in November: Eta and Iota.

Current Atlantic Basin Conditions

So far this month, the Atlantic has sent mixed signals for peak-season hurricane activity. Overall wind shear in the Caribbean Sea, a typical July Atlantic hurricane activity indicator, has been near average. This is in contrast to 2020, in which the 850mb zonal winds over the Caribbean Sea were much weaker than average. In addition, in contrast to 2020’s near-record low sea level pressures in the Atlantic in July, sea level pressures have been above average in the tropical and subtropical Atlantic so far this month. These indicators suggest that 2021, while likely to be an above-average Atlantic hurricane season, is likely to be considerably less active than 2020. A potential enhancing factor, as has been common in recent seasons, is that much of western Africa has been very wet over the last month. A stronger West African Monsoon (WAM) likely results in larger, stronger tropical waves that often take a long time to consolidate, but are more likely to develop into a significant hurricanes. In addition, Hurricane Elsa’s formation and intensification – becoming the earliest hurricane in the Atlantic MDR in the satellite era – is likely to be a red flag for the peak of the season. Tropical cyclones forming in the deep tropical Atlantic before August typically suggest thermodynamics are unusually favorable.

Cyclonic Fury’s 2021 Atlantic hurricane season forecast:

Cyclonic Fury also gives the following probabilities of activity. Right now, our forecast gives a 85% chance activity will be above the 1981-2010 30-year average, and a 60% chance of being “hyperactive”.

- Hyperactive season: 30% (Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) of 153 or greater, given the parameters of an above-normal season are also met. This is a very possible scenario, considering the overall favorable conditions.)

- Above normal season: 45% (This is the most likely scenario. With a warmer than normal tropical Atlantic and expected La Nina, this seems likely. However, the Atlantic MDR is somewhat cooler and the vertical wind shear has been higher than many hyperactive years.)

- Near normal season: 15% (Does not fall into the Below Normal, Above Normal or Hyperactive criteria. This scenario is unlikely, and will likely only occur if the dry mid-level air significantly suppresses activity.)

- Below normal season: 10% (This scenario is unlikely, and will likely only happen if vertical wind shear is unexpectedly strong.)

Cyclonic Fury also considers the following four years to be the best possible analogs for the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season. All of these years are second-year La Niña years since the ongoing active era of Atlantic hurricane activity began in 1995. It should be stressed, however, that every hurricane season is different and nobody should expect a “repeat” of any season.

- 1999 – 12 named storms, 8 hurricanes, 5 major hurricanes

- 2008 – 16 named storms, 8 hurricanes, 5 major hurricanes

- 2011 – 19 named storms, 7 hurricanes, 4 major hurricanes

- 2017 – 17 named storms, 10 hurricanes, 6 major hurricanes

- Analog average – 16 named storms, 8.25 hurricanes, 5 major hurricanes

It remains too soon to specifically say what areas are at greatest risk for the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season. So far, two tropical storms have made landfall in the United States (Danny and Elsa), while Tropical Storm Claudette became a tropical storm right after moving inland into Louisiana. Residents in hurricane-prone areas along the coast should have a hurricane plan ready, as the most active part of the season is only a few weeks away from beginning.

Cyclonic Fury July forecast verification

Cyclonic Fury has issued late July Atlantic hurricane season outlooks each year from 2018 to 2020. Our 2018 outlook significantly underestimated the activity of the season (though the major hurricane total was within the range), as we predicted 10-13 named storms, 5-7 hurricanes and 1-3 major hurricanes with an ACE of 80 +/- 20 units. Actual activity was: 15 named storms, 8 hurricanes and 2 major hurricanes, with an ACE of 129 units. Our July 2019 outlook verified somewhat better, as we predicted 12-16 named storms, 6-9 hurricanes and 2-4 major hurricanes with an ACE of 120 +/- 40 units. The hurricane, major hurricane, and ACE totals were all within our forecast ranges, though 18 named storms formed, two more than our maximum estimate of 16. In July 2020, our July forecast correctly anticipated a hyperactive season, when we predicted 18-22 named storms, 8-11 hurricanes and 4-6 major hurricanes with an ACE of 180 +/- 40 units. While our named storm, hurricane and major hurricane predictions were too low in 2020, our predicted ACE index of 180 was extremely close to the actual value.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.